By Simon Mannsi Project Manager, Helitronic Machines,

United Grinding (www.grinding.com), Walter-Grinding

Edited By Jim Benes | Associate Editor

There are several reasons that shops should consider CNC tool grinding, including that it provides the ability to produce high-quality, long-lasting tools and allows for flexibility and control of the process while saving them a ton of money.

Because in-house tool grinding is not part of shop’s core competency, careful analysis is necessary to be sure in-house grinding can be justified.

Shops must be able to dedicate a fulltime operator to run the machine. Training operators for CNC tool grinding is not difficult, but about five-years experience with CNC machine tools is required. And, operators do need to have a good working knowledge of tools.

Shops can justify a CNC grinder based on financial or flexibility considerations.

From a financial standpoint, a shop running standard tools needs to be spending at least $200,000 per year on the tools to be reground. However, shops that use special tools or change tools frequently can regrind these quickly with in-house capability.

Advantages of CNC grinding

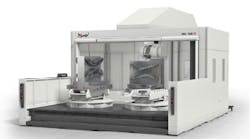

In-house tool grinding with manual machines presents several challenges. For instance, multiple machines are needed to grind one tool. A fluting machine, an O.D. machine and a pointing machine might be needed to grind one drill. This means multiple setups, whereas a CNC grinder needs just one setup for a complete grind. Similarly, a CNC grinder requires less floor space than multiple manual grinders.

Another concern is the workplace fouling created by the carbide dust that is generated in unenclosed manual machines. Most importantly, manual tool grinding relies on the skill level of the operator, and this is a dying art.

Finally, manual grinding takes much longer than CNC grinding. The data in Table 1, supplied by an automotive manufacturer, compare manual versus CNC tool-grinding times. As the tool geometry gets more complex, grinding times increase dramatically.

A problem with outsourcing is a lack of flexibility. For example, shops can run into overly long regrind times if they are running tools with unusual geometries, or they are involved in development work where tool features need to be quickly tweaked. Also, shops have little control over the quality of outsourced tool regrinds. When shops outsource, the regrind shop determines the scheduling of jobs to be run, so a shop may find itself at the end of a long line. Shops that grind in house have control over the priority and scheduling of tools to be reground.

The case for consistency

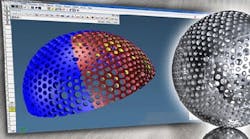

Not only is CNC grinding faster than manual grinding, it also makes better, more consistent tools because it does not rely on the skill of the operator. Many high-speed machining centers use tools with complex geometries, such as drills with different helixes on each tooth, or with helixes that vary along the tool. Such tools are difficult, or impossible, to grind manually with good results. With many software options, newer CNC machines can easily grind complex tool geometries.

CNC grinding of a drill ensures that there are no deviations in the diameter, space between teeth and radii of the tool so each tooth will cut evenly. Inconsistencies in these features can result in extra stress on individual teeth leading to reduced tool life. Tool consistency allows for long, uninterrupted runs, and tool changes can be scheduled to realize the full life of the tool. Also, the required number of tools for a job can be accurately determined from production schedules while tool inventories are reduced. Better tools produce less heat and vibration so machine tools last longer and require less maintenance while producing better surface finishes. Also, CNC grinding allows for the use of tougher tool materials allowing high cutting speeds and producing finer finishes.

Usually, manual grinding is done dry, while CNC grinding offers many coolant-delivery options The use of highpressure coolant prevents heat buildup on the cutting edge to allow for increased cutting speeds and extended tool life.

Speed reduces cutting costs

The most important factor in achieving cost-effective productivity is cutting speed, rather than tool cost or tool life. For example, industry data has shown that a 30 percent decrease in tool cost results in only a one-percent savings in cost-per-part to produce. Similarly, a 50 percent increase in tool life also results in only a one-percent savings. However, a 20-percent increase in cutting speed (even with a 50 percent increase in tool cost) results in a 15-percent drop in cost to produce each part. High-quality CNC ground tools can easily result in a 20 percent increase in cutting speed over speeds possible with manually reground tools.

Costs of outsourcing

The total cost of outsourcing tool regrinding involves the cost of production tools, plus the cost of spares to maintain production while the tools are being reground, plus service and shipping costs and, importantly, the cost of lost production in the event of a delay in regrinding service. These costs can add up to a significant annual burden. For example, consider a 0.5-in. O.D., 3-in. long, square, carbide endmill running on 20 spindles that cuts for four hours during each eight-hour shift for 250 days per year. With a 10-day turnaround time for regrinding, this tool would cost $206,000 per year to maintain by outsourcing tool grinding, Table 2. Annual cost to maintain this same tool running on 40 spindles, with a shorter duty cycle of two hours would skyrocket to $824,000.

Costs of in-house CNC grinding

The real cost of in-house tool grinding — including machine costs, operator costs and shop overhead — can be considerably lower than the cost of outsourcing tool grinding (Table 2). For example, the cost per hour of acquiring and running a $240,000 CNC grinder — considering typical costs of depreciation, interest, floor space, energy, maintenance and machine consumables — is $28.09 per hour. Typical operator-associated costs amount to $18.33 per hour, for a total of $46.42 per hour to run the CNC grinder. In the previous examples of a 0.5-in. O.D., 3-in. long, square, carbide endmill running on either 20 or 40 spindles, annual total in-house costs of tool regrinding are about one-fourth the cost of outsourcing regrinding.

| Tips for choosing a CNC grinder Be sure the machine has the versatility to grind all current and future tools you might need. Make sure software is easy to use and has 3-D simulation. The machine should be able to be set up offline so tools can be ground while setting up another job. When choosing a machine for regrinding tools, be sure it is also capable of also manufacturing them and has the required power and coolant pressure and capacity. Be sure the machine is rigid and accurate. Heavy machines are not necessarily rigid and moving heavy masses causes wear and it’s slow. Be sure you can share software programs with outside regrinders. Service and support are critical. Be sure local training and service are available. |