Tooling Manufacturers Are Changing From Tooling Vendors To Process Improvers.

In the U.S. metal cutting industry we believe there are millions of dollars to be saved in process improvements, and we prove that every day with our Productivity Improvement Program," says Brian Norris, vice president of marketing for Sandvik Coromant (www.coromant.sandvik.com).

"We are in the business of providing productivity benefits to our customers with a dedicated multi-brand team focused on improving the metal-removal process," says Muff Tanriverdi, president and CEO of Walter USA (www.walter-usa.com).

"We've done hundreds of Productivity Cost Analyses around the world in various metalcutting industries, and we've saved our customers an average of 20 percent in component cost everywhere we've done this," says Michael Parker, director of marketing and product development at Seco Tools (www.secotools.com).

When companies downsize to cut costs, manufacturing/ industrial/process/tooling engineers are frequently the first to go or, if the company is expanding, the last to be hired. Short-handed and no-handed manufacturing engineering departments are becoming the norm, and one result of this trend is that the employed engineers have little or no time to tweak processes to reduce costs and cycle times.

Fortunately, many cutting tool manufacturers are offering to step in and help fill this void.

For a number of years, cutting tool manufacturers have offered some process and cost analysis as part of their efforts to sell their tools. In the last three to five years, several of those manufacturers have changed their marketing focus: Instead of just selling tools, they are providing customers with productivity improvements that are paid for — eventually — by the sale of their tools.

This is not a matter of semantics, it represents a very real change in the emphasis of what is actually being provided to the customer.

About six years ago Seco used all of its past sales experience to create its Productivity Cost Analysis program. The program is a detailed analysis of metal-cutting operations that is designed to identify the true costs of a part so that the customer can see clearly where reductions in costs and cycle times can be achieved.

"Suppose you have a part that requires five operations to make," says Parker. "Most operators don't have a clear idea of where the cost has built up in those five operations. We analyze each operation in detail — feeds and speeds, tool change frequency, how long the carbide is actually touching metal, how long to index, everything. We then can cost each operation."

"Next, we figure out how to match changeover times to balance the use of the carbide, or we can increase speeds and feeds to bring down the carbide life but improve throughput. In the end, we can provide our customers with a very detailed look at how and where they can reduce part costs."

"After we finish the cost analysis we can prove it right on their equipment. We also try to optimize the whole solution so they don't have to use different grades of materials from different manufacturers, which has stocking and other hidden costs. Our system can even provide a printout predicting how many inserts per week should be used. We can couple that to a vending machine link for order stocking that will notify the tool-room supervisor if he starts to use more inserts than was predicted," Parker says.

Sandvik Coromant's Productivity Improvement Program has a similar focus.

"We look at all the processes used to make a part," says Norris. "It's a step-by-step methodology with a lot of science to it. Data gathering is non-invasive where the customer allows us to study the process, make some notes, ask some questions and observe the tool paths. We can do all that while they are making parts. Our main analysis is on the cutting tools, but many times we find peripheral elements that are affecting the cutting process."

"Workholding problems and coolants are two examples. We will make suggestions about those elements, but our competence and expertise is the cutting tool. In complex parts that might take as many as 20 different tools, we are often able to reduce that number perhaps to 15 or less. We consider this service as part of the added value we offer to our customer."

Norris noted that all shops — from tier-ones to small job shops — need to become more productive to remain competitive. However, he added that most of these shops are too busy or lack the resources to do this type of analysis themselves. Sandvik's program, like the other tool manufacturers' programs, is designed to provide those resources.

Walter/Titex/Prototyp is a relative newcomer to this type of focus. "We have been offering this type of service in Germany for more than 15 years," says Tanriverdi. "It was only three years ago that we started the Walter Productivity Services program here in the United States. We want to be in the business of providing benefits to our customers. We try to provide our customers with manufacturing expertise as it pertains to tooling and metal removal."

Walter's program has the advantage of being run as a multi-brand operation. Walter assembles a team of application engineers from its three companies based on each customer's needs.

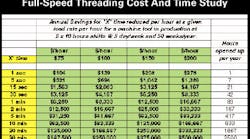

Other companies, such as Emuge Corp.(www.emuge.com), have a less formal but similarly focused service. "Because we are very specialized, we will do competitive cost analysis from time to time, says Alan Shepherd, technical director for Emuge. "Our primary approach, however, is to look at their operation and use our best experience to figure out how to improve it. We can run test programs at the customer's site or bring their material back here and test it on our own machine rather than tie up a customer's machine. Quite often, we will just ask for their material and threading requirements and specifications, run our costing programs and be able to show them the difference in tapping compared with thread milling."

When asked about actual cost savings, Shepherd says, "The savings can be huge. For example, if you are machining cast iron at 60 to 70 sfm, we can probably improve that up to 250 sfm. If the cost of having that machine just sitting there is a typical $100 per hour and I can cut just 10 minutes per hour off that, the customer will save about $83,000 per year amortized over two shifts and free up about 830 hours of machine time."

Shepherd also mentions their experience with an automotive engine production line. The line used 115 spindles to tap holes in the engine blocks. The company changed its $5 taps out at the end of each shift — a time-consuming process that had the line stopped while it was being done. By going to a $20 tap, the company could run between 20 and 30 shifts with the same taps. Not only was this a major cost savings, but it also dramatically improved the quality of the finished blocks.

"The problem with using the $5 taps was that they were starting to get pretty well used up by the end of the shift," says Shepherd. "That meant that some holes might not get tapped properly, and the last thing you want to experience is the inability to attach the alternator to the block further down the line because the hole was not properly tapped. By using the $20 tap, you could have much greater confidence that all of the holes were being tapped properly."

Examples of dramatic reductions in costs and cycle time from tools that use new technologies are commonplace, but unless the proper use of those new tools is fully understood, it becomes very difficult to reap those benefits. That is where the tool manufacturers and their productivity improvement/cost analysis programs come into play.

However, just because there is no engineering fee doesn't mean that the service is a free lunch.

Keep in mind that the only way these companies stay in business is to sell tools. Tool sales enable them to provide the service, and a shop's ability to take advantage of these services is directly related to the likelihood that the shop will become a customer of the tool manufacturer. One thing that all of the tool manufacturers have in common is their desire to form mutually beneficial partnerships with their customers. A shop that tries to get three or four companies to provide detailed cost analyses so that the shop can use each analysis to try to get the other companies to lower their prices is probably going to get what they pay for... next to nothing.

All of the cutting tool manufacturers interviewed acknowledge that they have to pre-qualify potential customers because the cost to provide these services is not low, and demand for the service usually is high. If a manufacturer does not have a reasonable expectation of getting an equitable price for its tools after proving that the customer will get a significant cost savings, then the cutting tool manufacturer is not likely to commit its best resources to providing the service.

The cutting tool manufacturers are looking for customers who are willing to look at them as business partners, not merely as tool providers, and prequalification is used to determine if it is worth spending time with that customer.

That said, these programs appear to be consistent in providing shops with savings of 20 percent or more. The services that the tooling manufacturers provide give shops a valuable resource that can immediately reduce costs, cut cycle times, improve part quality and free valuable machine time. And the charge for all of these benefits typically is the willingness to look at the cutting tool manufacturer as a partner rather than just a vendor.

| "Most operators don't have a clear idea of where the cost has built up in [their] operations. We analyze each operation in detail — feeds and speeds, tool change frequency, how many components have to be changed, how long the carbide is actually touching metal, how long to index, everything.... |

| "We will make suggestions about those elements, but our competence and expertise is the cutting tool. In complex parts that might take as many as 20 different tools, we are often able to reduce that number perhaps to 15 or less." |

| "If you are machining cast iron at 60 to 70 sfm, we can probably improve that up to 250 sfm. If the cost of having that machine just sitting there is a typical $100 per hour and I can cut just $10 per hour off that, the customer will save about $83,000 per year amortized over two shifts and free up about 830 hours of machine time." Alan Shepherd, Emuge Corp. |