Ethernet connectivity lets CNC machine tools talk to the rest of the factory.

Remote monitoring and diagnostics are just two benefits of networked machine tools. Programs like e-Diagnostics from GE Cisco reportedly increase machine uptime through a variety of proactive and rapid-response maintenance services.

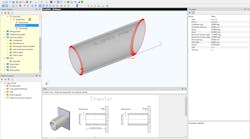

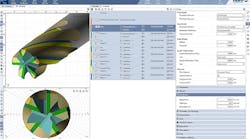

MDSI's OpenCNC V6.1 (left) is an unbundled software CNC that combines a soft CNC, soft PLC, and HMI. WinMotion (top) is a flexible soft motion/soft PLC for general-motion applications.

The Siemens 840Di is an open-architecture control with a Pentium processor that handles HMI functions and motion-control algorithms.

Series 16/18i Model B CNCs from GE Fanuc feature embedded ethernet in the basic system.

Machine tools are traditionally isolated islands of automation because many are equipped with proprietary computer numerical controls (CNCs) that make it difficult to network with other enterprise computer systems. But a revolution in CNC technology is opening them up, letting CNCs offer the PC functions and ethernet connectivity necessary to move data to and from networked systems.

By opening CNCs and providing an ethernet connection, shops can gather information from their machine tools to track productivity and more. In fact, says Phil Danner, vice president of technology, GE Cisco Industrial Networks, Charlottesville, Va., hooking CNCs to business-wide systems, such as MES and ERP packages, can provide numerous production advantages. Machine tool data can also be shared between end users and equipment suppliers, through such channels as GE Cisco's Remote Monitoring & Diagnostics (RM&D). "In the past, even if a supplier had a service-and-repair expert on site, time was still needed to troubleshoot faults," says Danner. "Now, with an RM&D system, the supplier can monitor the equipment from anywhere in the world, pinpoint fault sources, immediately resolve the problem or dispatch expert service, and return the machine to production in a fraction of the time previously needed."

Rajas Sukthankar, project manager for Motion Control Systems, Siemens Energy & Automation Inc., Elk Grove Village, Ill., points to other advantages of ethernet connectivity. For one, it provides a seamless integration into many existing IT infrastructures so shops can gather CNC information and pass it to a higher-level system within a factory automation infrastructure. "The ethernet is also common to the office environment, so those on the plant floor don't have to learn something new," says Sukthankar, "nor does the shop have to buy something special to connect the CNC to the front office."

Another benefit to ethernet connectivity is that it lets shops store large programs on the local hard disk of a PC-based controller or transfer these programs, on-line, directly to the CNC. "Thus, effectively, the memory constraints that existed in the past within the CNC architecture have been removed with the next generation of CNC controllers," says Sukthankar.

An industrial ethernet also provides a high-speed, low-cost connection that is getting faster and cheaper all the time. "The advantages to ethernet connections involve speed and bandwidth," says Scott Rohlfs, director of marketing for motion products at Mitsubishi Electric Automation Inc., Vernon Hills, Ill. Bandwidth refers to the rate at which information transmits over the network.

So why aren't all new CNCs talking to the rest of the company? Part of the problem is that although many CNC vendors offer ethernet ports on their new controls, they are still working on standardizing application protocols so that CNCs can talk to other computer systems in a plant, including other CNCs. But standardization will be tricky because many CNC vendors support different protocols for networking at different levels.

Generally, CNC equipment has three levels of networking: information, control, and device, explains Rohlfs. The information level is for sending data from machine to machine or back and forth between the office environment and an operator's station. The control level, on the other hand, controls equipment, such as one controller synchronizing its operation with another controller or peripheral controllers associated with the total operation. Finally, the device level is for controlling I/O — the CNC's onoff status of relays, lights, and solenoids, for example, or the monitoring of limit switches and operator control buttons.

Ethernet interfaces aren't always used at all three levels. CNCs and PC-based systems from Mitsubishi, for example, use an ethernet interface on the information level, which involves transfer of data such as operating programs, tool information, and statistical data for monitoring equipment in the office environment. "We support a variety of interfaces on the device and control level," says Rohlfs. "This is where information is sent over a network to control devices or peripheral equipment within the system. Some of the interfaces are proprietary to Mitsubishi. But we also support some industry standard networks. Whatever the customer requires."

Networking concerns

One of the issues with ethernet connectivity, comments Mark Devonshire, market manager, IMC business, Rockwell Automation of Milwaukee, is that it's not "deterministic." Determinism guarantees transfer of data between two devices in a specified amount of time. "To guarantee determinism," says Devonshire, "a network must be designed that way."

Devonshire adds that determinism might not be an issue "if you're looking to pass information, such as large files and non-time-critical data, to and from a host system for monitoring machine tool capabilities and status. Then ethernet is fine. The key is to understand your requirements and pick the network that meets your needs."

Security issues also need to be addressed, especially as companies look at the Internet as a control network. "The Internet is cost-effective, large, and public. How do we ensure that that pipe we build is only used for passing information between the right people?" asks Tom Mathias, manager, open systems for GE Fanuc.

"Set up intranets," says James Fall, president of Manufacturing Data Systems Inc. (MDSI) of Ann Arbor, Mich. It's an Internet-like network independent from the outside world. He says companies can build intranets with the appropriate firewalls. In addition, a level of security can be found in the CNCs themselves. MDSI, for example, provides nine levels of security in its OpenCNC product, which lets the control lock out certain functions at specific levels. Nine levels let shops assign passwords and log-ins to the control so certain personnel only have access to specific information. This might mean a production operator would have different access than the person setting up the machine or those doing maintenance.

Choosing a control

For shops looking to connect their machine tools to a factory-wide ethernet network, a PC control is key. Devonshire says shops can use PC-based software that leverages standard communications tools available in their office. Users should also see if an ethernet connection is standard with the control or an add-on. And the protocol the control supports is important because it determines how the control communicates information back and forth to other systems.

According to Sukthankar, shops can choose a PC-NC CNC or a CNC with a PC front end. The former is a PC that looks after both the NC and the PC functions. It is integrated into one piece of hardware. The other CNC has a separate PC front end connected by a bus to a back end (an NC that stays in the machine panel/cabinet).

MDSI's Fall adds another type of control to the list — the software CNC. His company's OpenCNC combines a soft CNC, soft PLC, and human/machine interface (HMI) in one application and requires no proprietary hardware or motion-control cards.

Whatever the selected control, says Wayne Kotania, product manager, CNC software and communications for GE Fanuc, consider the CNC's application and software support. He recommends that the CNC follow common programming standards and use open tools and technology that easily distribute and share data and information.

Fall agrees that it is important to use standard off-the-shelf ethernet and Internet technology in hardware and software. But what is also key is access to machine and process data — data that users can define and also change as their processes change. Too many controls and data-collection technologies limit customer choice in data, says Fall, both the quantity of data that can be collected and access to it. Too many require that the user go back to the control vendor for permission to change the data items collected. He recommends that a control provide user control of and access to unlimited machine and process data.

Machine data involves maintenance and machine diagnostics, and process data centers around machine operation. With this information, shops can scrutinize the entire machine cycle to see what affects cycle time and part quality.

Despite the new control technology, the major barriers to letting CNCs use ethernets or the Internet lie on the shop floor. According to Fall, as much as 90% of the installed base of machine tools lack some form of connectivity to the rest of the enterprise. Shops can certainly buy new machines with built-in control connectivity, but it doesn't take care of the installed base of NC/CNC machine tools. For those machines, the choices include retrofits with a new control or adding a DNC-style interface to the machine tool. The latter solution, says Fall, is a limited "patch" to the manufacturers' needs.

"These hardware patches provide limited access to the machine tool," comments Fall. This, he cautions, means someone has to integrate another PLC to feed data into the hardware patch. "And patches don't make the machines run any faster." He recommends upgrading the control for several performance benefits along with ethernet connectivity.

Another problem with networking machine tools is the wiring. Most CNCs are linked with RS-232 rather than ethernet connections, making them less conducive to networking.

Because running new cabling can be expensive, shops could investigate wireless solutions. But for any wireless deployment, says Danner, conduct a wireless survey. This half-day process looks at things that can affect connectivity — electrical noise, metal walls that act as antennas, and so forth. "Typically, in a factory, you're going to be okay. But have someone take readings over the entire site to place access points," comments Danner. Access points are devices in central locations in a plant that are plugged into a local area network. They send and receive wireless signals.