The popular media are full of gloom-and-doom reports of the loss of millions of manufacturing jobs to other countries and as a result of the recent recession. The manufacturing-sector job loss is estimated at 2.9 million since July 2000. However, a paradox exists within these statistics. Even though manufacturing in general has, and is, facing serious layoffs, there is a rapidly growing need for highly skilled, technically competent employees capable of exploiting new technologies and supporting increased product complexity. Most jobs that have been lost to countries with cheaper labor costs have been manual labor, such as assembly-line jobs. Those that remain and need to be filled are the more intellect and reasoning-based jobs.

"In spite of dramatic changes in factory conditions, the old stereotypes of backbreaking labor and grimy working conditions persist."

Tom Whelan, Silverstone Group.

Eighty percent of manufacturers surveyed in a study of workforce issues in manufacturing conducted by the National Association of Manufacturers (NAM) report they face a moderate to serious shortage of qualified job applicants, in spite of serious layoffs throughout the industry. More recently, 36% of NAM members say they currently have unfilled employment positions because they cannot find workers with the math, science, and technological aptitude needed in manufacturing today. The problem is not a lack of employees, but rather a shortfall of highly trained, skilled employees with specific educational backgrounds and skills.

The need for highly skilled workers is fueled by several factors. To meet competition from around the world, manufacturers must compete less on cost than on product design, productivity, flexibility, quality, and responsiveness. This puts a premium on employee skills, motivation, and commitment — workers who can think on their feet and solve problems. "A country of Wal-Marts just doesn't cut it," says Beth Solomon, associate director of media relations at NAM. "You can't have an economy that doesn't make things. Plus, we have enormous technological and geographical advantages over anywhere else in the world."

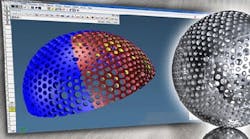

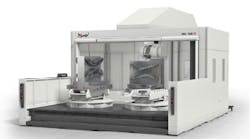

Technology is expanding exponentially throughout the industry — from design and production to inventory management, delivery, and service. The introduction of CNC machine tools has changed the nature of the work of machinists. Now, a machinist has to be computer literate and understand basic electronics and physics. Employees at all levels must have the skills to deal with the technology inherent in complex environments. For example, Mable Sebastian, director of graduate-employment services at Louisville Technical Institute, says since May, 2003, about 80% of potential employers visiting the campus are looking to hire workers from the mechanical-engineering program who can diagnose and fix problems in a automated assembly line.

Changing demographic factors contribute to the looming employment crisis in manufacturing. For instance, the Baby-Boomer generation of skilled workers will retire within the next 10 to 20 yr, creating the need for an estimated 10 million new skilled workers by 2020.

In a survey commissioned by Advanced Technology Services Inc., about two-thirds of the 94 senior manufacturing executives surveyed said the projected retirement of 40% of their skilled labor force during the next five years will cost, on average, $50 million. Yet 46% of respondents with more than $1 billion in revenue predict their costs will be more than $100 million over the next five years.

"The looming skilled-worker shortage is an unwelcome threat to the nation's manufacturing base that needs to be addressed at multiple levels, from better educating the next generation of factory workers to improving the public's image of plant work," says ATS President Jeffrey Owens.

Manufacturing's bad image

There's no doubt that manufacturing has an image problem. Students asked to describe images associated with a career in manufacturing responded with phrases such as "serving a life sentence," being "on a chain gang," or "slave to the line," or even being a "robot." Almost unanimously, they saw manufacturing opportunities to be in stark contrast with the characteristics they desire in their careers. Thus, they do not plan on careers in manufacturing.

"Most young people have in mind a 20, 30, or 40-yr-old manufacturing model," notes Tom Whelan, a principal at Omaha's Silverstone Group specializing in human-resource development. "The dangerous, dirty, labor-intensive assembly lines of the 1950s are gone, replaced by robotics and intelligent systems requiring high-tech skills. In spite of dramatic changes in factory conditions, the old stereotypes of backbreaking labor and grimy working conditions persist. Manufacturers have failed to show how they've modernized, embraced new technologies, and involved workers in management and product development."

One reason manufacturing is perceived as a declining field is that employment figures reflect the number of manual-labor and assembly-line jobs being replaced by robots or moved outside the country. Most people don't think about the higher-level jobs remaining.

Another misconception is that manufacturing offers only low-paying jobs. According to the Department of Commerce, the average salary-and-benefit package for manufacturing workers was $62,700 in 2003. The national average for all jobs was $51,000. David Huether, a NAM economist, says the disparity stems mainly from health benefits, not wages, which are only marginally higher in manufacturing. Manufacturers provide health benefits to 87% of their employees — more than any other sector except government.

Safety, or the lack of it, is another misunderstood manufacturing issue. Over the past decade, manufacturingemployee injuries have declined by 36%. The main reason for this decline is that business owners are taking voluntary steps to address safety issues. A 2004 NAM survey found that 89% of responding companies have written safety and health programs, up from 70% six years ago.

"I got into this to learn a skill so I would be able to have a successful career. Getting older, I realized I needed to know something to get through life."

Rashe Randall, apprentice machinist

One region's efforts

The skilled manufacturing-worker shortage in southwestern Pennsylvania is typical of many regions across the country. A survey of manufacturing companies in the area conducted by Duquesne University's Center for Competitive Workforce Development and New Century Careers (NCC) — a nonprofit training organization — found that 71% of the job vacancies uncovered in the study were for production workers. The best of these opportunities are for skilled jobs that require vocational school or technical or communitycollege training. Most employers surveyed said it was either "very difficult" or "somewhat difficult" to find skilled production workers — a growing concern as their current workforce of Baby Boomers nears retirement and will need to be replaced.

NCC was started in April, 2000, by Duquesne University's Institute for Economic Transformation and the Steel Center Area Vocational-Technical School in West Miffin to establish and manage workforce-development initiatives. "Manufacturers told us of their problems, and we built programs that are solutions to their needs," says Marisol Wandiga, marketing manager at NCC. In 2001, a regional collaborative was formed to begin advancing the high-technology skills of incumbent workers and prepare more entry-level workers for skilled manufacturing positions.

Four Workforce Investment Boards, representing the nine counties comprising the southwestern Pennsylvania region, are charged with assessing and monitoring changes in the supply and demand for labor, gaging the effectiveness of local workforce — development strategies, creating linkages and developing regional collaboration to enhance service to employers and job seekers, and promoting regional training efforts in workforce development.

Training is offered on a continuum, with each step adding additional skills and offering career-advancement possibilities. The program begins with the Partnership for Regional Innovation in Manufacturing Education (PRIME), an industrydriven coalition that unites Robert Morris University, California University of Pennsylvania, and several area community colleges. The initiative, aimed at the middle and high-school levels, presents manufacturing as an occupation with attractive career-path potential and develops a feeder system of future manufacturing employees. Next, NCC's Manufacturing 2000 training program is offered for unemployed and underemployed workers to prepare them to take skilled entry-level positions as machinists or welders. Then, NCC's Manufacturing 2000 Plus program trains displaced or incumbent workers in skills identified by manufacturers as areas of shortages. Finally, the linked training system offers college-level courses for those wishing to achieve higher positions in the industry, including degrees in manufacturing technology and manufacturing engineering.

The NCC programs are a door-opener for students. Rashe Randall, a machinist who earned a Manufacturing 2000 certificate and is completing an industry apprenticeship program, reflects, "I'm from Clairton, and I got into this to learn a skill so I would be able to have a successful career. Getting older, I realized I needed to know something to get through life."

Another resource for area metalworking shops is the machinist apprenticeship program of the Pittsburgh Chapter, National Tooling and Machining Association (NTMA). It provides 576 hr, over four years, of competency-based training to apprentices who earn nationally recognized National Institute for Metalworking Skills (NIMS) credentials. To become a NIMS-certified machinist, toolmaker, CNC setup programmer, or certified journey worker, trainees must complete a curriculum, pass a written exam, and demonstrate satisfactory performance in a number of required competencies. The program builds on 24 sets of NIMS standards and credentials and enables employers to apply the NIMS credentials as milestones within their apprentice training. Employers are able to customize training to meet their special needs while maintaining the integrity of apprenticeship training.

Some educational resources are aimed at highly skilled persons already working in manufacturing, but with a need for specialized technical training. For example, Kennametal University conducts courses at the company's Quentin C. McKenna Technology Center designed to provide metalworking professionals with the skills to gain optimum performance in metalcutting operations.

"Hiring associates with the right technical skills is a critical issue for my company, and as technology becomes more pervasive, skills are going to be at an even higherpremium."

W. R. Timken, The Timken Co.

Jodi Sullivan, a tooling-systems manager at General Motors, Tonawanda, N.Y., says, "The Comprehensive Application Engineering Course at Kennametal University provided exactly what I needed to improve processes in my job. The instruction I received on cuttingedge materials and how they fail allowed us to optimize our processes and gain significant cost reductions."

Kennametal University is a member of the Advanced Manufacturing Center Collaborative (AMC2), a broad-based collaborative of organizations that highlight the importance of manufacturing and the need for manufacturing-related education and careers in southwestern Pennsylvania.

An innovative program under the auspices of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania's Department of Community and Economic Development offers a flexible regimen designed to give students the exact level of education they need, while employers get trained workers to fill positions to keep them competitive. Known as the 2+2+2 Workforce Development Pipelines, the program consists of three segments — two years as a junior and senior in high school, two years in an associate's degree program, and two years leading to a bachelor's degree. After any two-year segment, students can either head into the workplace or go on for more education. If they decide to go on, or go back to school later, credits earned previously apply to the next degree.

Help from the FedsIn October, 2004, U.S. Secretary of Labor Elaine L. Chao announced an advanced manufacturing-worker training effort under the President's High Growth Job Training Initiative totaling more than $24 million to address the workforce needs of the industry. The Department of Labor (DoL) recognizes the challenges facing manufacturers are far too complex for one institution or industry sector to solve alone. The DoL's Employment and Training Administration (ETA) supports comprehensive partnerships that include employers, the public workforce system, and other entities that have developed innovative solutions to the workforce needs of the advanced manufacturing industry. Almost $500,000 of the $24 million is earmarked for NAM's "Dream It, Do It" careers campaign aimed at informing youth, parents, and educators of the rewarding career opportunities in advanced manufacturing. The program, launched in the Kansas City, Mo., region, creates tool kits and strategies that will be replicated in at least five additional manufacturing-intensive regions of the country. As part of the project, a targeted marketing campaign will be launched along with a pro-manufacturing alliance among business leaders, economic developers, educators, and various civic organizations. To stimulate and assist apprenticeship programs, the ETA's Bureau of Appreticeship and Training (BAT) registers apprenticeship programs and apprentices in 23 states and assists and oversees State Apprenticeship Councils (SACs), which perform these functions in 27 states, the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, and the Virgin Islands. Government's role is to safeguard the welfare of apprentices, ensure the quality and equality of access of apprenticeship programs, and provide integrated employment and training information to sponsors and the local employment and training community. |

Grassroots skills developmentAMT and more than 1,000 corporations, trade associations, and labor unions support the national SkillsUSA program that prepares high-school students as high-performance skilled workers and provides quality education experiences in leadership, teamwork, citizenship, and character development. About 13,000 teachers and school administrators serve as professional SkillsUSA members and instructors. The Precision Machining Technology (PMT) Competition at SkillsUSA is designed by industry leaders committed to attracting new highly skilled workers to a career in precision machining. Annual competitions are held locally, regionally, and nationally, with the final 2005 championships held in Kansas City, Mo., June 22-24. Contestants compete in NIMS Level I and II manual machining skills and knowledge areas including operation of manual milling machines, lathes, drill presses, and surface grinders. Contestant knowledge of CNC programming skills using a PC is evaluated. Related knowledge and skill in the areas of engineering drawing interpretation, technical math, machining practices, use of precision measuring/hand tools, and ability to communicate verbally using proper industry terminology are also part of this competition. To stimulate interest among middle-school students ages 11 to 14 in pursuing math and science courses, the U.S. Department of Commerce and NAM launched the GetTech program. The campaign features a teen-friendly website — gettech — public service announcements for radio and TV in the top 100 metropolitan areas, and materials for teachers and students distributed to 14,000 middle schools. "Manufacturers have been talking the talk for a long time about how people are our most important resource," says Jerry Jasinowski, NAM president. "GetTech is our way of walking the walk, by dedicating resources to break down barriers that keep most kids from pursuing the academic subjects that will lead them to careers in manufacturing and technology." W. R. Timken, incoming NAM chairman and CEO of The Timken Co., Canton, Ohio, a sponsor of GetTech, comments, "Hiring associates with the right technical skills is a critical issue for my company, and as technology becomes more pervasive, skills are going to be at an even higher premium." Harry C. Moser, president of Charmilles Mikron, Lincolnshire, Ill., and a tireless crusader for promoting education to train the workforce of tomorrow, says, "Although a wealth of manufacturing career promotional materials exist, few manufacturers, high-school instructors, guidance counselors, and community college machining instructors know about and use these materials. This is why we have devoted the Careers in Manufacturing section of our website — charmilleusus.com — to catalog promotional information and materials from a variety of sources. Our plan is to link everyone who wants to promote careers in manufacturing to all providers of relevant promotional materials." Moser believes that promoting the financial advantages of pursuing a high-skills career in manufacturing to parents and guidance counselors is powerful ammunition to stimulate interest among students looking at possible careers. "With a bachelor's degree in English, a student can expect a median annual before-tax lifetime income of $40,000, compared with $60,000 for a worker with an associate's degree in manufacturing technology or an apprentice," explains Moser. "However, the return on investment/yr — considering expenses and lost income during training — is 6% for the BA in English, 39% for the AS in manufacturing technology, and 125% for the apprentice." |